BY CHARLES PRESTON AND JEREMY BORDEN

In the wake of the November 2015 release of a video showing a police officer shooting teenager Laquan McDonald 16 times in the back, many Chicagoans demanded that City Council—especially the 18 aldermen of the Black Caucus, whose constituents are most affected by police violence—overhaul what the McDonald video highlighted as a broken system of police accountability.

Those who favored more drastic changes viewed Mayor Rahm Emanuel as complicit in allowing police officers to mistreat people of color with impunity; they delivered a powerful mandate for aldermen to address this crisis independently from the mayor’s office. However, the more progressive legislation pushed by members of the Black Caucus and others largely failed. Activists and police accountability experts said their proposed reforms were watered down before being added to the mayor-sanctioned legislation that eventually became law. Why?

For the Defender, City Bureau analyzed data and interviewed politicians, staffers and other political experts about the efficacy of aldermen, especially in the Black Caucus, on the issue of police reform in the last two years. The analysis reveals a microcosm of the dysfunction that has plagued Chicago for years. Police reform stalled because of a system that consolidates power in the mayor’s office, while City Council stays occupied by mostly mundane ward-level issues like business and parking permits. The majority of aldermen are hesitant to flex any independent political muscle—staying focused on what one observer called their “fiefdoms,” leaving control of citywide issues to the mayor.

“Patronage was not all bad; there were bad parts of patronage,” Ald. Roderick Sawyer said. “I equate the demise of our communities with the advent of Shakman. Things started happening when we were not able to provide jobs for our communities.”

In front of the cameras and in public, the conversation about reform in late 2015 and early 2016 centered around whether City Council would embrace CPAC, the Civilian Police Accountability Council. Popular with activists, CPAC would elect a citizen-led board to oversee the police department and the beleaguered Independent Police Review Authority, the agency charged with overseeing investigations into police misconduct.

Inside City Hall, the reaction was one of wait and see.

“It was pretty clear to most aldermen that the ultimate ordinance to pass was going to come out of the mayor’s office,” said one City Council insider who asked for anonymity because they are not authorized to speak to the press on this issue. “Folks came into [the police reform debate] with the understanding” that any proposed legislation, outside an Emanuel-approved bill, could only pressure the mayor’s office toward stronger oversight and accountability procedures, the insider said.

Ald. Roderick Sawyer, the chairman of the Black Caucus, pointed out that aldermen don’t have their own legal departments to write and vet independent legislation.

Because aldermen’s legislation ultimately must go through the mayor’s law department, most wait for cues from the mayor before they decide what to do, according to a former political aide who spoke on condition of anonymity to describe the City Council’s internal process.

Emanuel’s press office did not respond to requests for comment.

Both Alds. Leslie Hairston and Jason Ervin pushed ordinances, which were eventually combined into a single proposal called the Independent Citizen Police Monitor—less aggressive than CPAC but supported by many advocates for strong oversight. The ordinance was largely written by University of Chicago civil rights attorney Craig Futterman; Hairston worked behind the scenes with the Black Caucus to vet it, and in all, it had 32 co-sponsors (64 percent of the 50-member City Council).

But ICPM never received a vote. A version of its proposals was included in the legislation pushed by the mayor’s office—COPA, the Civilian Office of Police Accountability—which won approval in October 2016 from all but eight aldermen. COPA, however, passed without the increased funding, stronger independence from the mayor’s office and transparency measures that Futterman and others had pushed for.

“The thing you have to understand about when an ordinance comes out, it’s basically for the press,” said the former staffer, of the City Council’s process. “And people just sign onto it [as sponsors]. A lot of them aren’t even planning to vote for it.”

Hairston and others were disappointed that COPA didn’t include some of the ICPM’s stronger measures. In a recent interview, Hairston said the city let an opportunity pass by. “I think we had one time to get it right,” she said. As for Emanuel, “if the mayor breaks promises, there are no consequences.” Ervin could not be reached for comment.

While aldermen shaped and prodded the legislation in ways some observers say are unprecedented, the end result was largely business as usual: a process dictated by the mayor, where the Black Caucus did not stick together.

Chicago’s political system does not have to work this way. In fact, by charter, the city has a “weak mayor” form of government, where significant power is vested in the city’s 50 aldermen.

In a lengthy, candid interview, Ald. Roderick Sawyer, chairman of the Black Caucus, said that aldermen do not yield as much power as they used to. Sitting under a framed picture of his father, Eugene Sawyer (longtime alderman and, briefly, mayor after the death of Harold Washington), the now-sixth ward alderman says he remembers when people would approach his father and tell him that because he got them a job with the city, they avoided the streets and saved their life by providing steady employment.

Aldermen doling out jobs to would-be voters was considered unsavory and, eventually, illegal. The practice ended after a series of lawsuits in the 1970s that resulted in what would be known as the Shakman Decrees.

“Patronage was not all bad; there were bad parts of patronage,” Sawyer said. “I equate the demise of our communities with the advent of Shakman. Things started happening when we were not able to provide jobs for our communities.”

Sawyer wants aldermen to become independent policy makers, leaving smaller ward-level items to be handled by city administration, he said. He works on legislation himself and sets aside some money for help with those efforts, but wants more resources for his office and Council as a whole to work independently from the mayor.

City Council data, collected by Legistar and analyzed by civic transparency firm Datamade, show that a very small percentage of the body’s actions affects the set of laws that govern the city as a whole. City Council has passed more than 18,000 pieces of legislation since the McDonald video was released. Just 1.4 percent deal directly with the municipal code.

98.6 percent of ordinances (yellow) do not amend municipal code. Only 1.4 percent (red) do so. Click to expand.

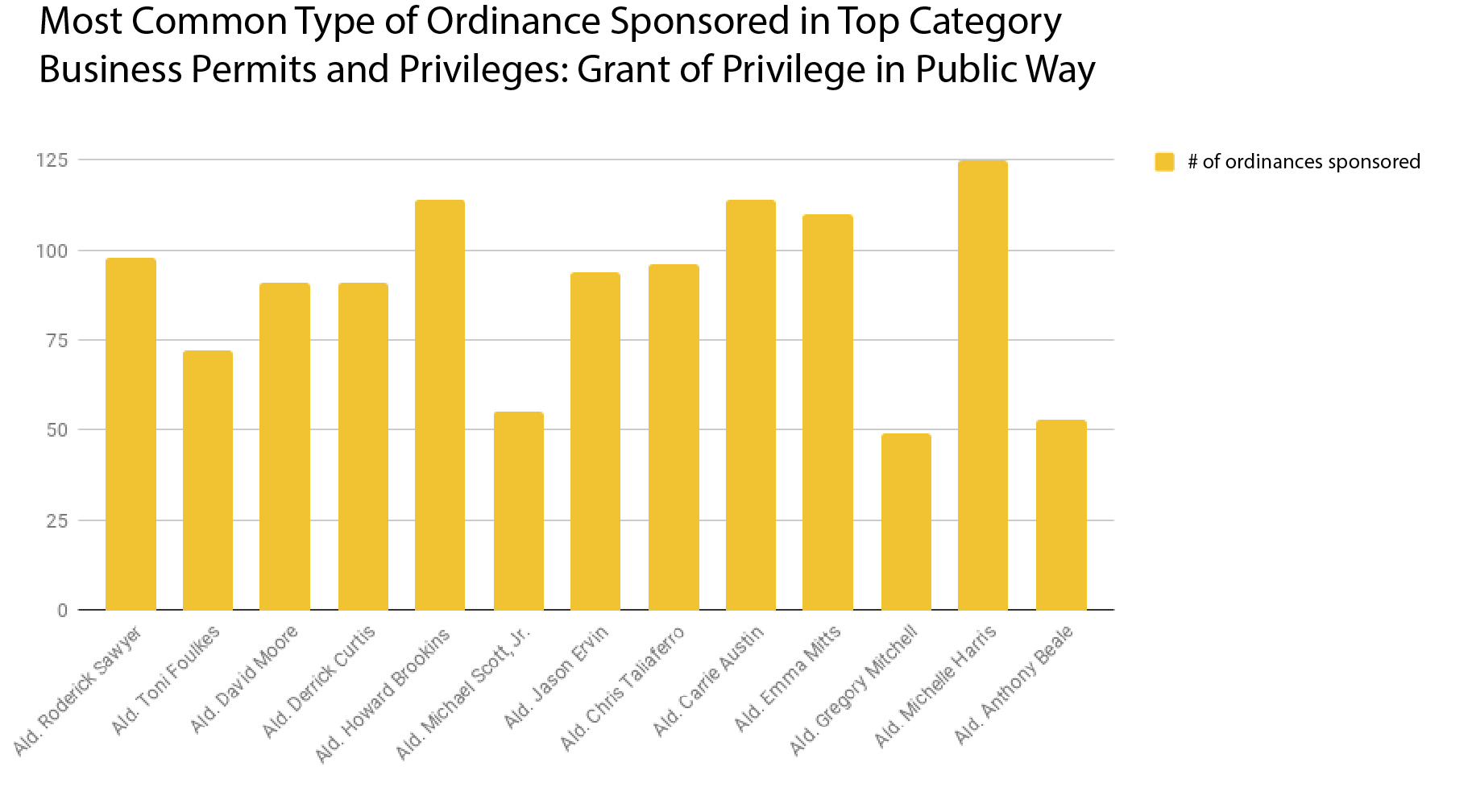

Among the different types of ordinances recorded by Datamade, Black Caucus members’ most commonly sponsored items deal directly with residents (such as handicapped parking permits) and business permits (such as a “grant of privilege” to allow a store to hang a sign over the sidewalk). A City Bureau analysis of the data showed that “residents” ordinances were the most commonly sponsored type of bill for five members of the Black Caucus: Alds. Willie Cochran, Walter Burnett Jr., Pat Dowell, Sophia King and Leslie Hairston, all of whom had handicap parking permits as the top sub-category within that type of ordinance.

“Business permits and privileges” ordinances were the most commonly sponsored type of bill for the remaining 13 members of the Black Caucus, and “grant of privilege” was the most common sub-category for that type.

Beyond wielding more sophisticated legislative resources than aldermen, the mayor also has significant power to exact retribution on City Council members who cross him. He can appoint City Council committee chairmen, push candidates to run against aldermen, cut off Democratic Party campaign dollars or starve their districts of resources or funding, politicos and aldermen said.

Ald. Leslie Hairston, who was outspoken on the issue of police reform and blasted the mayor for pushing inadequate measures, didn’t answer directly when asked about political retribution. “It’s not easy, it’s not fun, but it is what it is,” Hairston said. “Malcolm X was not treated well, Martin Luther King was not treated well, and I’m not comparing myself to them … I look at the struggles of those that came before and it gives me the strength to deal with it.”

Chicagoans might expect that the Black Caucus—like similar groups at the state or national level—use its 18 votes to ensure African American issues are well represented. But that’s not often the case.

City Bureau and Datamade found that of the current makeup of the Black Caucus, the group has only voted together six times in recent years—all on ceremonial, uncontroversial legislation.

Charles Thomas, a former ABC7 political reporter and now talk show host who has been reporting on the Black Caucus and City Council for decades, said because the caucus is based on race rather than ideology, they are hardly all ever in agreement.

“What do they do? To be honest, not much,” Thomas said. He believes the biggest issue for the Black Caucus is an informal rule known as “aldermanic privilege.” Essentially, aldermen are usually unwilling to interfere with projects and issues in their colleagues’ wards. In practice, it means black aldermen do not stand together on issues where they should be aligned, such as school closings and minority hiring for big projects. For example, the Black Caucus may choose to not interfere with multi-million dollar downtown projects out of respect for the aldermen in those wards, rather than ensuring minorities are hired, Thomas said. “They respect each other’s little fiefdoms in Chicago City Council and that rule supersedes anything else, including the caucuses,” Thomas said.

Where Does the Black Council Go From Here?

“The alderman have to do a better job of representing our interests. I think the only way they can do that is to govern more transparently. [They] have a responsibility to report to the Black community about cases about police brutality.”

Dr. Valerie C. Johnson

Associate Professor and Chair, Political Science Department at DePaul University

“They are too closely aligned with Rahm Emanuel. We have a plethora of Black experts that they can sit with, like Dr. Kelly Harris, that they can talk policy with. But they don’t take advantage of the Black expertise in their wards. I think that’s really wrong.”

Robert T. Starks

Associate Professor, Northeastern Illinois University Center for Inner City Studies

“After Laquan McDonald happened, they should have served as a strong check and balance against Mayor Emanuel and the police department. But they did not provide any strong critique of the mayor or put any pressure on the mayor.”

Dr. Kelly Harris

Interim Dean of the Honors College and Professor, African-American Studies at Chicago State University

But Sawyer sees that changing. Younger aldermen are more interested in taking leadership in writing legislation, he said, and in recent months, the Black Caucus has made strides in getting its priorities front and center. For the first time, the mayor’s office is coming to the Black Caucus looking for input on legislation—and makes changes based on that input.

While acknowledging the limits, Sawyer gave the Black Caucus a “B-minus” grade in terms of accomplishing its goals. But black activists in the city are not as forgiving.

Anton Seals, a community organizer, said that residents ultimately must demand more, get involved, vote and agitate. He’s not sure they will. “In America, the power of comfort wins all of the time,” he said. “People, humans, want to be comfortable. They want to be able watch TV and eat some pizza. There is only certain crowd that gravitates towards activism.”

William Calloway, a South Shore activist who led protests demanding the McDonald video’s release, said African American communities have been devastated by a lack of leadership. “I have no confidence in [the Black Caucus],” Calloway said.

I think they have done nothing to really uplift our people, and I think the African-American community deserves new leadership.”

This report was produced in partnership with DataMade and the Chicago Defender.