BY DARRYL HOLLIDAY and HARRY BACKLUND

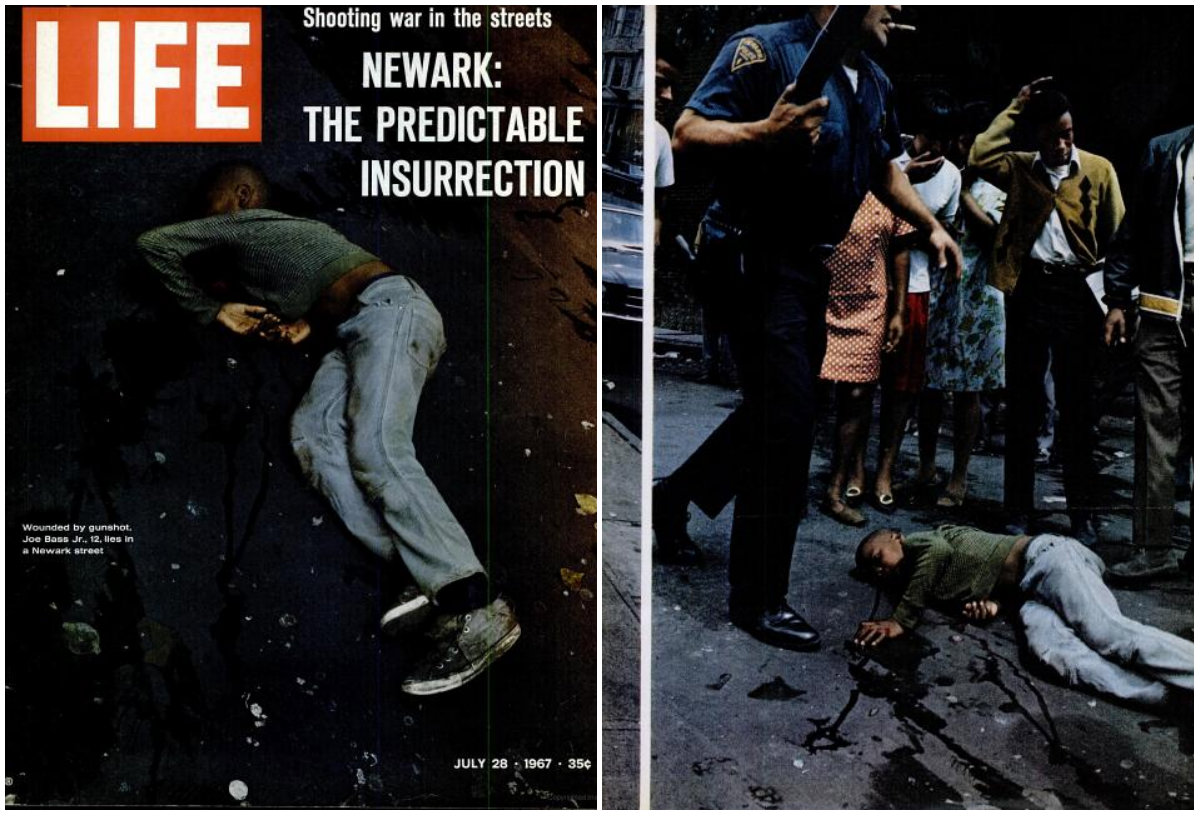

Edward “Buzz” Palmer has been at this moment before. When he first saw the July 28, 1967 cover of Life magazine—a black boy lying dead in the street, shot by police—Palmer was a young black police officer in a racially divided city, working in a department that still segregated its squad cars.

“It was the times,” Palmer explains. “The times create the conditions. King had been assassinated, Malcolm X had been assassinated. What it pointed out was the need for the black community to be protected. We saw all this killing going on.”

The July 28, 1967 cover of Life magazine featured a photo of 12-year-old Joe Bass Jr., dead on a Newark street after a shoot-out between civilians and police. (Source: Creative Commons/Life Magazine)

Palmer was moved by the image to form the Afro-American Patrolmen’s League, the first African-American police organization of its kind. He spent two years in the department before handing the role over to Pat Hill, who quickly had her own challenges to face.

“I knew the culture of the police department when I went in,” Hill said. “I knew the disparity in treatment of black officers, and I spent a lot of my time fighting against policies in the department.”

A call for more black police officers

Last Wednesday morning, Hill stood with other retired black police officers at a news conference to call for the hiring of more black officers and a federal investigation into the Chicago Police Department and the Independent Police Review Authority, the civilian body tasked with investigating complaints of police misconduct. Since then, Mayor Rahm Emanuel has replaced the head of IPRA, and U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch has announced a civil rights investigation of the police department.

At their news conference, the retired officers cited the persistent under-representation of African-Americans in CPD as a root cause of tensions between black neighborhoods and the police department. According to police records, the CPD is 23 percent black, compared with 33 percent of the total Chicago population.

The news conference came three days after the firing of former police Superintendent Garry McCarthy, and 10 days after the release of a dashcam video that shows 17-year-old Laquan McDonald being shot 16 times by CPD Officer Jason Van Dyke. The shooting, captured and repeated on an unending loop online and on TV, was yet another moment of historical reflection for Hill.

“For me this is about the third time. It’s the third go-around. Certain concessions are always made and everything goes back to being business as usual: scandals, police brutality [and] discrimination in the department,” she said. “ I can’t be as optimistic as a person who’s going through it for the first time.”

Like the cover of Life Magazine in 1967, Hill said the latest symbol of police misconduct — the image of McDonald; a black boy lying dead in the street, shot by police — is yet another moment of striking cruelty and a call for meaningful reform.

Much like the ousting of McCarthy, past Chicago police scandals have also led to resignations and promises of reform. In 2007, CPD superintendent Philip Cline resigned amid an uproar over video footage of Chicago police beatings. The film included a widely-circulated Youtube clip of an off-duty officer beating a female bartender on the Northwest Side. Ten years before, superintendent Matt Rodriguez announced his retirement amid a series of scandals, including police corruption and brutality allegations.

Hill and Palmer sought to reform the department through diversifying its ranks, but young black activists today argue that policing itself is oppressive.

“As a black cop or brown cop, you are in a position of power over the group of people you are policing,” Janae Bonsu of The Black Youth Project 100 told The Chicago Reporter last month. “Black police antagonize us. Black police still profile us.”

Palmer and Hill agree that the problem is systemic — “violence has a handmaiden, and the handmaiden is poverty” as Palmer puts it. But Hill takes issue with the idea that an officer’s race doesn’t matter for the community they work in.

“The village needs warriors to protect it, not settlers to occupy it.” —David Lemieux

“So many young people — so many young black people especially — are taking the initiative to be heard. In that respect that’s a positive,” she said. But the young activists weren’t there in 1967, she noted — while being actively engaged in the current moment, they lack the historical perspective that comes with age.

“They really can’t take it too far [back] … There’s a big difference between white police and black police. Our upbringing is totally different and we’re treated differently. We’re suspended and punished at a higher rate — we’re scrutinized differently.”

David Lemieux, a retired black police officer and 26-year veteran of CPD, added to the chorus of calls for systemic change and improved relations between police and the public.

“In order for there to be any change in the relations between the community and the police, the infrastructure has to be saturated with people that represent the community,” he said. “The village needs warriors to protect it, not settlers to occupy it. Who are the boots on the ground? That’s what’s important.”

The history of black officers in the Chicago Police Department is long and often checkered. In 1872, Chicago appointed the first black police officer to serve outside of the South, but black officers in the early years of the department weren’t permitted to wear uniforms, and were instead restricted to plainclothes duty, mostly in black neighborhoods.

Still, black officers were better represented in Chicago than in most American cities. Between 1872 and 1930, Chicago appointed more black officers than any city except Philadelphia, and in 1940 the city had its first black captain—one of only two in the country. Yet black officers couldn’t arrest white citizens, and black sergeants were assigned exclusively to supervise black officers.

Pat Hill was among a group of retired police officers who on Dec. 2 called for a federal investigation of the Chicago Police Department. Hill, who retired from the force in 2007, is the former executive director of the African American Police League, formerly the Afro-American Patrolmen’s League. (Max Herman/Chicago Reporter)

Pat Hill was among a group of retired police officers who on Dec. 2 called for a federal investigation of the Chicago Police Department. Hill, who retired from the force in 2007, is the former executive director of the African American Police League, formerly the Afro-American Patrolmen’s League. (Max Herman/Chicago Reporter)

A scandal over police involvement in a string of burglaries ushered in the era of O.W. Wilson, a prominent police reformer who reorganized the department around principles of efficiency rather than patronage. Wilson promoted sergeants and recruited more African American officers, but his retirement in 1967 preceded a new era. The 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., and Mayor Richard J. Daley’s order to “shoot to kill” rioters, caused mounting racial tensions. “Shoot to kill” was the backdrop for the formation of the Afro-American Patrolmen’s Union by Buzz Palmer.

The AAPL brought a lawsuit against CPD in 1973 for discriminatory hiring and management practices, and won in 1976 with a judge ruling that CPD must hire more blacks and women.

Hill noted that while Wednesday’s news conference achieved its goal of having black officers speak out, it failed to comment on the systemic nature of racism in the Chicago Police Department by focusing too closely on a single individual.

A similar issue is raised in the handling of McCarthy by Emanuel. Hill and others didn’t support McCarthy’s hiring when he was confirmed in 2012 and while she agrees with his dismissal, she sees the way politicians are “kicking him on the way down” as political posturing.

“I don’t think it’s about one individual,” she said. “I think it’s important for black officers currently in the department and retired to take positions on this because the black community needs that.”

Palmer and Hill also agree that the black community needs the Black Lives Matter movement, including Chicago-based groups like BYP100.

“We’re living in a new era,” Palmer explained. “One of the reasons why things always died down was because blacks did not have access to the media. Now they have access to social media. When Ferguson went up the newspapers didn’t cover it, but all at once all these young people were on their smartphones and they got a million hits and people had to pay attention to it.”

He added, “This is not an issue that is going to go away.”

This report was published in collaboration with The Chicago Reporter, a nonprofit investigative news organization that focuses on race, poverty and income inequality. Additional reporting by Will Cabaniss.