What challenges have you encountered in working on Black mental wellness that led you to consider alternative approaches?

The way that mental health is approached is through behavior, which is not the best [approach]––particularly for Black folks. What we are experiencing is about way more than behavior. There’s so many factors: systemic, community-level, individual, generational family patterns. We have a long history of experiencing trauma.

I love Dr. Joy Degruy. She is known for [the theory of] Post-Traumatic Slave Syndrome. She talks about how Black folks have never had a break to heal or develop in a way that they deserve and should because of the constant attack from white supremacy, racism, and other institutions.

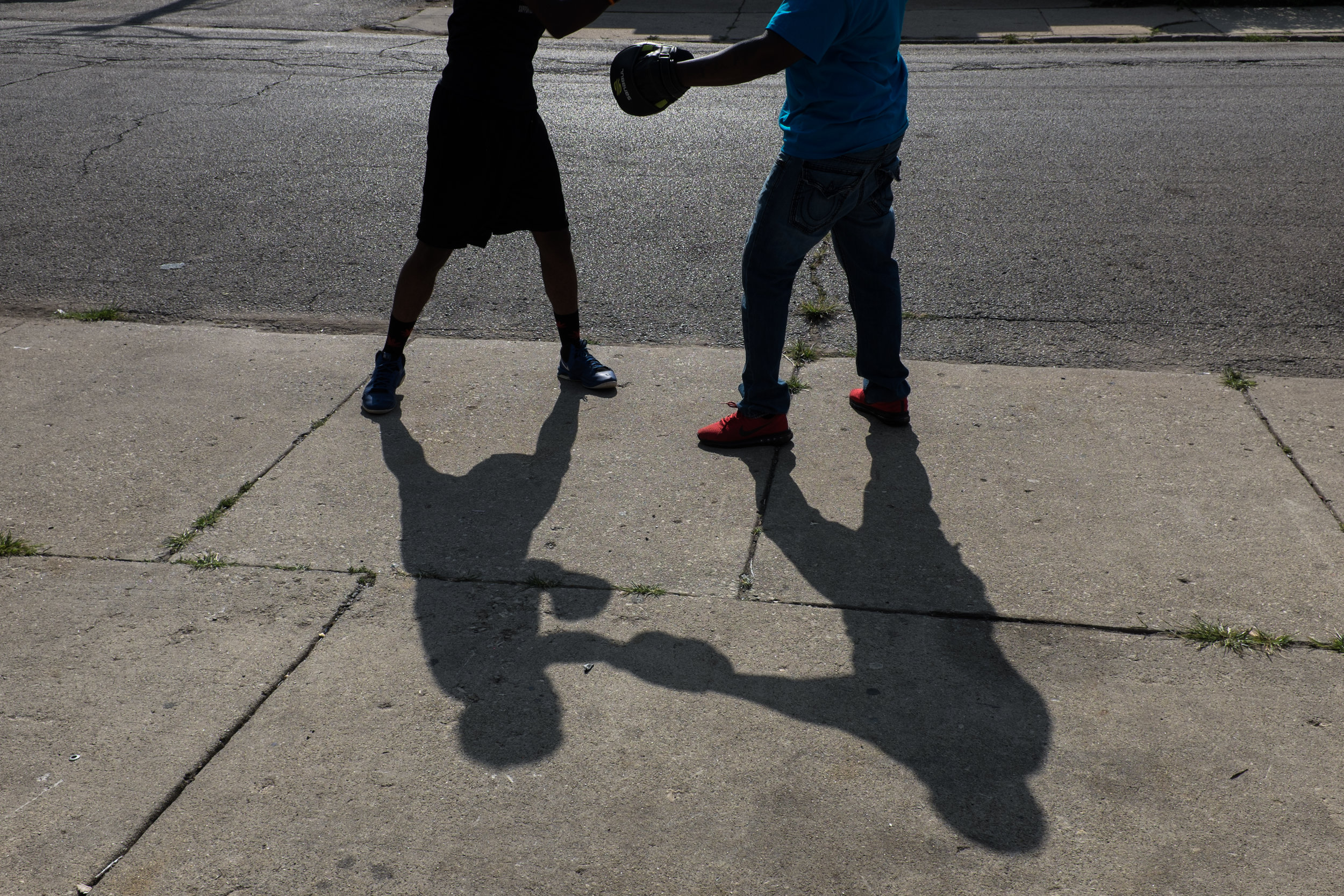

With Black girls and boys, any time they are acting out or doing things outside of what makes people comfortable, it’s labeled as a “behavior problem.” What I understood working with young men is that they are expressing the pain they are experiencing in their communities.

What makes Sista Afya different from mainstream mental health care?

Sista Afya has a community support model that anchors mental wellness through community. Basically, no one is going through things alone. Whether it’s a support group or educational workshop, people are depending on each other.

Sista Afya pushes advocacy in our model as well—Black women being able to advocate for and amongst themselves for the wellness care they need. I’m still fine-tuning and developing this model.

I believe the people who are most affected by these conditions should be the leaders. I have a bipolar disorder, which is a very severe and serious mental condition. No PhD, no license can trump real experience. I believe that’s what makes Sista Afya a success. People hear my story and see where I stand today and go “Wow!” They understand I have bipolar but I maintain my mental wellness and practice what I’m preaching.

How does Chicago factor in what you see or work with daily? The city’s violence is always in the media and I wonder if that plays a role in mental health.

I’m not a Chicagoan. I wasn’t born here. But before I came to this city, I thoroughly studied its history. I’ve never seen a place where so many actions were taken to suppress Black people mentally through institutions. This affected family, then community, then individual.

The violence in Chicago is sensationalized. There is a good buck to be made off of violence and trauma. In the mental health field, people are making money off our pain. What better way to heal ourselves than to collectively come together, identify generational and community-level issues, and demand things from institutions that are complicit in our oppression?

What role do you think mental health plays in substance abuse?

Substance abuse is usually the expression of something someone is trying to avoid, something painful, or something traumatic. When someone uses heroin, they know that heroin isn’t good for them. When you think about the communities who have the most prevalent substance abuse, those communities usually don’t have the mental health resources or institutions that are needed to support full and healthy lives––things like a grocery store, jobs, and adequate housing. If you live in a community where you’re suffering from not having these things, you go to substances to sedate or express that pain.

Before the two-year Illinois budget impasse led to huge funding delays and other issues in the state’s health care system, Mayor Rahm Emanuel closed six mental health clinics. Where can people go for assistance?

I’ll share a couple. Dr. Obari Cartman’s Association of Black Psychologists, Chicago’s Association of Black Social Workers, Breaking the Silence of Mental Health, Sista Afya, and Black Lives Matter Chicago Communal Healing are all partnering together to create a directory by the end of this year. People who live in Chicago can put in their ZIP code and find a Black practitioner in their area. I think that will help people to know what’s available. Someone can be providing mental health services right in your neighborhood and you may not even know it. Instead, you may think you have to go all the way downtown or outside of your community.

Of course, Sista Afya’s website is a resource: people can click on different topics that are particularly important to Black women and get an information sheet about resources that may benefit them. I would also say Psychology Today is another good resource for finding a therapist until we release our directory.

There are a couple of really good nonprofit organizations across the city such as Trilogy Behavioral Healthcare, Metropolitan Family Services, and Thresholds. Those organizations are a lifeline for people who may not be able to afford insurance, providing high-quality mental health care. That’s a really big thing in our community. People don’t have insurance or they have Medicaid and cannot receive the best care they need.

Does the state owe us the mental health clinics and services? Absolutely. But we also know that history can repeat itself, and they can snatch it away at any time. We have to think about how we can rely on our own expertise and our own talents in our communities to make sure people are connected to resources to sustain mental wellness.

What would you like to see from the state? Can you think of new ways for the state to be impactful for community alternatives to traditional health care?

I think they failed already by trying to provide services through clinics that they can shut down at any time. We deserve and should demand that government fund mental wellness services, particularly through Black practitioners. But we also have to prepare when they don’t. This is the time for us to embrace something that will be long-lasting.

When I say “Sista Afya 2018,” what comes to mind?

Consistent presence. I think the first year of Sista Afya was a lot of figuring out the things people like and don’t like, while still staying true to what we want to provide to the community.

I want to make [Black Mental Wellness Weekend] an annual event, so every Veterans Day weekend people will know to clear their schedules. In the summer of 2018 we will be having the next Black Mental Wellness Expo. I’m also planning monthly events so people can stay plugged in through Sista Afya. Every month people can expect a workshop that is free or very low-cost.

I will also say, innovation. This year we tried to creatively think of ways that we can bring people together around mental wellness that is not intimidating, but fun, caring, and supportive. This will be another year of innovation.

Do you believe that we are getting better identifying mental health issues in our community?

Yes! I think the future’s very bright. Chicago has so many talented people that can address our community’s needs. People are talking about it.

When I first started Sista Afya, people would come up and say to me, “Well, what are you going to do about the stigma? How are you going to get people to come to your event?” So I thought about my own experience, about what pulled me into caring about mental health. I started to think, how can I make mental health fun, simple, accessible, and centered on us? Once you do that, people feel comfortable.

I think in Chicago people have been waiting for a movement, and I’m so happy to be a part of it.

This report was produced in partnership with the South Side Weekly. Listen to an interview with Camesha Jones and Dr. Obari Cartman on the November 7 episode of SSW Radio, the Weekly’s radio hour on WHPK.

![Joe Boyd, 82, gets some sunshine outside the senior building he lives in in Auburn Gresham. “A lot of times as you get older, [people] leave you, you know what I mean? One by one,” said Boyd, a veteran who often reflects on his life. “I’ve been ups](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56cfdde2c2ea51668ffa109d/1544646849550-XH211LBMOPZU8WJIAB3A/Joe-Boyd-3.jpg)

![Yvette Gresham, 59, helps Lillie Smith get ready. For the past four years, Gresham has been Smith’s homemaker. She is paid by the City. Smith qualified for a homemaker after a heart surgery. “I don’t know if [some seniors] got help because I see the](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56cfdde2c2ea51668ffa109d/1544646863384-MX6PGFQ9QKSWO02ZXKBH/Lillie-Smith.jpg)